Yaloo works with animation, video, installation, sculpture, digital fabrication, VR and projecjection mapping to create spatial narratives while also challenging conventional understanding of the screen and cinema.

Her moving image work uses multiple collaged layers with references that range from everyday consumer goods, pop culture and medieval painting to create complex animated textures and patterns. Her work ranges from haunted houses, Remoto (2018), to digital ruins Yaloo Castle Site (2018) to distinct ways that expand her animation practice from VR landscapes to silk scarfs.

She repurposes and recycles everything from objects to package design, creating her own counter narrative to mass production and global branding. From ginseng to beauty products, Yaloo examines how a place can market itself as a product through exploitation of cultural goods. Her work uses marketing conventions and remodels them into a Yaloo-sanctioned universe to sell an experience. While using and exploiting technological tools to produce multiple variations of her own work – like different versions of a software system – Yaloo creates a unique vision and world.

She received her MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2015 and has participated in multiple national and international residencies. Her works have been included in solo and group shows in Chicago, New York, Seattle, Santa Fe, Vancouver, Quebec City, Malmö, Dresden, Fukuoka and Seoul.

Yaloocharm for Heart, 3D video installation (with chromadepth glasses), Liege, Belgium, 2018

LZ: How did you get started working with Animation?

Y: I think it was really natural for me to be interested in moving images. Because, you know, I grew up with TV and it was something that always inspired me. But my unofficial creative training happened when I first took a moving image course and learned how editing worked. That led me to create something that matched how things were in my head. On the one hand, it was like the magic was broken – it became real – but at the same time I realized that animation was something I could actually do. I mean it would look different, but I could do the same thing. That was a new kind of magical experience.

And since then I’ve always wanted to work with animation and moving images. I’ve always been inspired by media and pop culture. I’m trying to challenge my inspiration, because when you just watch you become the consumer. But when you process, digest, and make it into your own thing, then you become the artist. I think the way that I do things could inspire others, or provoke them to be critical of their daily media experience. I think that is the only way to survive because our lives are too saturated these days.

LZ: Within your work animation is used in multiple ways – as instillation, film, virtual reality, or in a combination of viewing experiences. What role does the spectator play in relation to this?

Y: I started as a single channel video maker and then I slowly moved to installation. It was very natural for me to have more of a sculptural and physical presence for my moving image. I mean in cinema it makes sense to walk into a dark room and sit in a comfortable chair and just immerse yourself into the screen. I really like that too, but at the same time when your body is visible I really like how you can engage with the screen in a different way. You could walk around it, you could walk up to it, you can some sometimes touch it, and I like that.

I’m learning how to use VR to have some kind of artistic presence. I think it’s really important because there aren’t that many independent artists working with it yet. When I talk to people who are into VR these days, I can’t really talk to them, because we are interested in completely different things. But I decided to take VR on as a challenge because I think it’s really important that artists with slightly different perspectives – who don’t necessarily have training in a tech school, but who think critically – are able to access and use these tools. I think that really helps, or I hope it helps in the long run because digital technologies are advancing so fast. It’s really important to have individual voices as much as possible. That’s why I try to do it. And how I do it is really simple. When people see it, they say “what is she doing?” Because I am hacking how things work and at the same time showing other people, “oh this could also be done.” It can inspire others. That’s why I try to engage with the physical space and these new technologies.

LZ: When you approach your work, do you think of it as sculpture or as video, or animation? How do you conceptualize the different components that make up the installation?

Y: I’d say it is more sculptural. Because there isn’t that much narrative filming in time, it’s more about the work having a big presence that is also engaging with the space. That’s also something I think about because I struggle with time, and lack of financial resources. I have to juggle and compromise here or there. This happens when I’m animating because I don’t have a lot of time. So I have to ask myself if I see it as a sculpture or as an animation. Often within my work, the sculpture has to have more time-based elements.

Where there is animation, it unfolds over time and tells something different, so that people will look at it longer. Or it can grab someone’s attention. Within the whole installation it is more about a physical engagement, where it’s more important to have people walk around and feel the whole thing.

Yaloofarm, videomapping on the attic wall, Vermont Studio Art Center, 2015

LZ: How did you get into projection mapping?

Y: I wanted my animations to be physical. I didn’t like the rectangular shaped screen. Installation really involves space and the human body and it doesn’t really make sense to sit there and look at the screen. So that’s where I started. I asked myself how do I make the screen more alive and physically engaging.

I really want a spectator to be a part of the space. The screen plays a huge part of the design of the space. Screens on the wall…that’s no different from cinema. I really like it when I can walk around, and also become immersed in the work. So I think it’s important for the moving image that the screen also has to have some kind of presence like a persona.

LZ: To be a character in and of itself…

Y: Yeah, exactly.

LZ: In some of your installation’s, you’ve created screens that are large sculptural shapes that you can move around in the space and interact with in a very playful way. Can you tell me more about what inspires your exhibition design?

YalooPark, Yes! Sebum, Documentation, 2017

Y: I’m very inspired by theme park designs, the fun house, children’s museums, or haunted attractions, because I see them as a ‘multi-art’ where your body is immersed and your mind is directed to engage within the space. As the creator you have to direct the spectator in how they walk, how the narrative unfolds as they are walking, the lights, the size of the space, or the size of props, or how far they walk – I really like these constraints that you can give to the viewers, and then how you can build up narratives from that.

For the last few years I’ve been doing residencies, and I’ve been fortunate enough to go to new places that I’d never been to, and be given space to work. For the last two years most of my work was based on my daily experience, from when I was in a new place, where I’d walk around, meet new people, eat different things and gather source material. I developed a body of work from that. When I put on a show in these places, for a lot of viewers it was odd and familiar at the same time because the materials were very basic and already present as media around them. I use materials that you can’t see everywhere else, so the stuff that could be very familiar for local viewers, is not necessarily for people outside of that. I think that kind of play between materials and place is a big part of my work.

When you are walking from home to transit, there is a ton of stuff happening. The fun house is the same but it is more constrained. I like that an installation can take cues from the fun house as wells as mimic how you live your daily life. As the creator you have full control on how someone could feel while they are walking and engaging with the space. I’m still learning, and I think I’m getting better at it. But I really like to think of every single possible thing that could be happening. To offer the viewer a narrative that they can enjoy. I think it should be entertaining, that’s a natural way for someone to be immersed in an experience, but it doesn’t mean that it’s necessarily fun. With a haunted house, it’s scary, thrilling and fun. I’m really interested in engaging a larger range of emotions. For example, I’m not into horror movies, but I’m training myself to get into them more. They are a really good example of playing with a viewer’s emotions with similar parameters as those you’d find in the setup of a narrative in a space like a fun house. I look at all sorts of things but for these kinds of installations, a lot of the elements come from my daily experience.

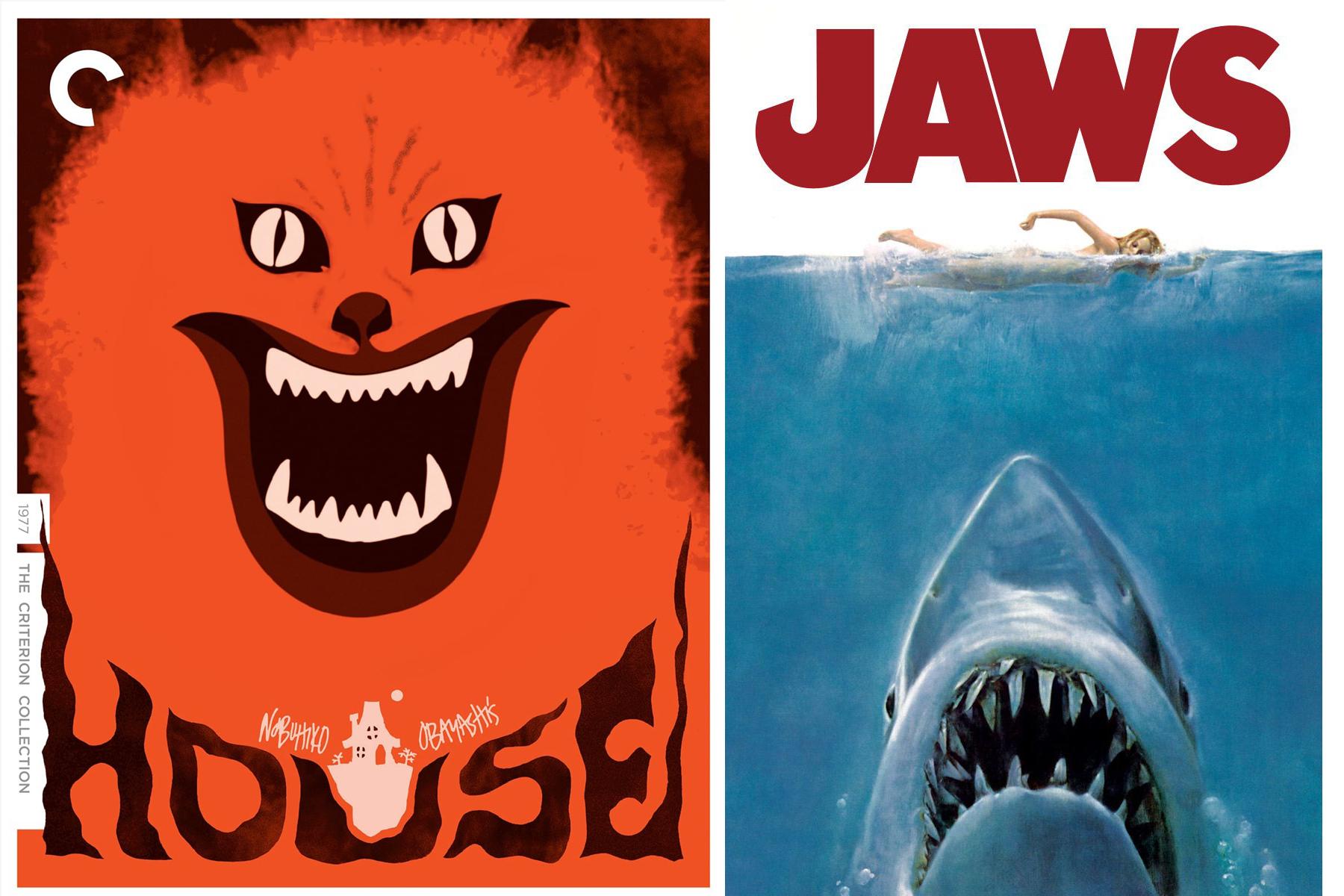

LZ: Have you ever seen Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1977 film House?

Y: Oh yeah it blew my mind when I saw it!

LZ: It’s one of my favourite films. It has a great use of optical printing, painted backdrops, and it plays with how the audience experiences space.

Y: Yeah totally, I grew up with manga, so for me, it just blew my mind because I saw it while I was in school in Chicago. First of all, I’d never seen any old japanese movies, and when I saw Hausu, I could see all the manga influence and a lot of comical references that I was so used to. But being able to see it on the screen changed my world because I was able to see where all the sources were coming from. I read an article about how it was the director’s attempt to create something, to compete with Jaws (dir: Steven Spielberg, 1975). And to me, I was like that’s amazing. To think that the director wanted to compete with Jaws and this is what they come up with! That’s amazing.

LZ: Where did Yaloo come from? You insert your name into a lot of the titling for your exhibitions like Yaloo Castle Site (2018), Yaloohouse, Yes! Sebum (2017) or Yaloofarm for Romansusan (2016). What is its significance within your work?

Y: The name itself doesn’t have a meaning, but I wanted to come up with a name that I could give to myself. I grew up hating my name because there were always the same family names growing up in Korea. When I was young, I wanted to be artistic and different. Because I gave my name to myself, I’ve become more actively engaged in every decision I make. I’m the only one who can give meaning to my name and I started building my work from there. For me, art and life are the same thing. It’s a struggle to make a career as an artist. There are lots of compromises you have to make because we live in a capitalist system.

LZ: It’s as if you are trying to create a Yaloo State where you highlight all kinds of different products that exists within our consumerist culture but you’re creating the Yaloo sanctioned version of that.

Y: Yeah, exactly.

LZ: A lot of your moving image works are a collage of so many different tiny moving elements. Do you work in 3D? Where are you finding your source images? How do you build your digital moving image pieces?

Y: I often work with found materials. Before working with VR, I used to take pictures of everything and download tons of youtube videos and cut and paste them multiple times until I liked the textures and forms. I would use multiple processes. Sometimes I’d draw, or take pictures and then print them, and then take pictures of them, and then a picture of a picture. Or sometimes I’d screen print them and take a picture of it, or I’d heat press them and then take a picture of it. It was a process of multiple versioning. And since I started with VR I’ve been sculpting off of found objects. For example, some of the lace patterns I used in the VR sculptures in Yaloo Castle Site that I worked on while in Japan, I got from Japanese female sanitary pads. I’d never seen such conventional ‘girly’ sanitary pad design in my life. And they smelled really flowery so that you could smell them two ailes way in the grocery store. Those lace patterns and overpowering smell were part of the the image that they sell to girls who are scared of smelling like blood. So I sculpted off of the lace designs on the packaging and then made them into an animation.

LZ: Can you tell me more about you project Yaloo Castle Site?

Y: Yaloo Castle Site was an installation I created for a cherry blossom festival in a real castle from the 16th century that had just been rebuilt and was reopened at a festival in Fukuoka, Japan. My piece was actually in the castle. I wanted it to be site specific, so I started to think about what would it mean to have an artwork in the ruins. A ruin is something that lives in multiple temporalities – the past, present and future. So I decided to create Yaloo Castle Site, which is a magical historical site that exists in the past, present and future at the same time. It’s ruins that are based on Yaloo’s universe, where all the buildings and sculptures came from the stuff I collected and my experiences while living in Fukuoka for three months. I had 7 rooms. There were sculptures of things you might find in a castle: A gate, a fallen chandelier, an indoor/outdoor sculpture garden, and a big fountain. VR was a huge part of the work, because while I was on this residency I was training myself to use VR, and I sculpted everyday, so the elements came from all the sculpts that I did.

Fukuoka is the biggest city to the south of Japan and it is pretty conservative. There is a division between male and female, which is made very visible through the available clothing options, down to the packaging of consumable goods that are marketed to a particular gender. I was reacting to how femininity is portrayed through the work, and also that’s part of the reason why I invited a local Butoh dancer. He is a first generation Butoh dancer from the Kyushu region. He is an older dancer, and wears a wedding dress when he performs. When I talked to him and heard his personal story, he told me all about how he had to do certains things to survive as an artist throughout his life. He didn’t really say why he wore a wedding dress but for me it’s really obvious. He wore the dress to reject that divided sexuality in Japan. There was also a Nam June Paik piece (Fuku/Luck,Fuku=Luck,Matrix) in Canal City – a giant shopping mall, which has his biggest TV walls in Japan. But most of the TV’s are dying. While on the residency I saw it everyday so I naturally thought about what it means to work as a media artist where your stuff isn’t going to last as long as your lifetime compared to other mediums like painting or sculpture.

Red Ginseng Series, Pink Noise Popup, One Space, South Korea, 2018

LZ: Within so much of your work there is a complex relationship between all the different actions and how they fit together to create a hyperreal moving textile. It’s as if a narrative occurs through rhythm and the way in which the different shapes and structures are working in relation to each other. This is a very special way that only animation can let you approach storytelling.

How do you approach narrative within your work. Is it something you stray away from or is it intuitive? With more traditional animation filmmaking there is a lot of specific planning around timing and story. How do you approach narrative and timing in your work?

Y: I mean, within my process the narrative is very clear in my head. I see where things are coming from and how I am versioning them into a piece. But the viewers are only seeing the product of it. So I don’t think people understand my whole process, but I’m more interested in how they engage with the end product. I give them a hint, through the title or through the text, but they can use their own imagination to engage with the work. I think my type of narrative is more based on shapes and textures rather than story.

LZ: You use a lot of loops and different kinds of movements – choppy, short and quick versus fluid and slow – that are all mixed together. When you’ve created your own patterns and textures, or used found source material, how do decide on the kinds of movements that each of these forms will have?

Y: I like finding patterns. When I start making, the whole process is really about me looking for the right shape and giving it the right animated pattern. And then when they are all combined they all have different animated looks and they create their own animated microcosm where everything is moving. It often feels like, I animated all of the stuff and it’s like I am zooming out from the earth. This is how I image that the earth would look like, where everything is tiny, and they look like patterns and they are all moving but you can see multiple patterns going on. I imagine that I’m really far away from it.

LZ: It reminds me of Eva Szasz’s animation Cosmic Zoom (1968), where there is a mosquito that bites a person and you zoom in to an extreme close-up of the molecules that we are made up of and then back out to the farthest possible point imaginable in the universe.

I always find with animation that people always want to know exactly how something is made. There is an inherent magic to animation that as soon as someone sees it, they want to know all the “tricks”. One of the aspects I appreciate most in your work, is that there are so many textures and layers. I’m always unclear on what’s made in 3D or what’s flat, because it’s all compressed onto a single plane. The play between depth and flatness is really interesting. Especially when you’re changing the structure and material, by projecting your work onto large sculptural shapes, which again mimic the forms within the work itself. I think this creates a visually dynamic interplay between what’s moving, the screen, and your sense of depth.

Y: Oh that’s really interesting, because yeah for sure there are constant clashes between flat and 3D in my work. In the end it goes on the screen and becomes flat. But I work with a variety of images that are flat but also many of the elements within the images are also 3D. I work with VR and I create 3D objects but in the end, I flatten them by creating a stop motion out of them, so there is a constant back and forth. I like the idea of how versioning plays within my work. I always shift back and forth from video to picture, picture to video, or with 3D images. I go back and forth between multiples like machinery – like from embroidery machine to sewing machine, to video camera, to laptop screen grabs, and I’m making the same thing and using the same materials but I go through multiple versions. I think that is something that is only possible in our time, which is super exciting. But that is also where the idea of play comes in, because I play through all these possible mediums that are given to me.

LZ: How did you start putting yourself into the work that you are making? In animation there is a tradition of the animator inserting themselves into their illusion. Like the live performance screenings of Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur where he would have this call and response with the the dinosaur, and then got ‘injected’ into the animation. How did you come to put yourself into the worlds that you were making?

Y: I think it was just my childish attempt of, “oh it’s mine, so I’m going to be in it.” In my very first animation, I was actually in it as a character and I used stop motion and travelled through the little sculptures that I created. At that time it was the only way for me to make work. It was like me imagining things, and me travelling through it – so I had to be in it as a character. At the same time, people questioned me about it and would ask why I didn’t use other actors. When I tried it felt wrong. For one, I didn’t know how to invite other characters into my work, and I didn’t know how to direct others because it was about being spontaneous in these spaces that were my imingainations. It was difficult to translate that to someone else. But these days, since i’ve been working with many people doing residencies, and doing community engaged projects, it became natural and often necessary to bring other people into my work. For example, for the project I did in Japan, the butoh dancer I interviewed also performed for one of my sculptures. He is one of the characters in my TV tower in Yaloo Castle Site. So yeah, now I’m more flexible about working with ideas from the world and not just from within my head.

Yaloo, New Millennium Workout Routine, 2014

LZ: I wanted to ask you about how you conceived of the New Millennium Workout Routine? The movement is very hypnotic. In watching it, it’s as if it becomes something other than the workout routine. It is very different from the other work that you’ve done because the movement is so melodic and slow. It’s so controlled and uniform, whereas in your other work the movement is still choreographed.

Y: I learned the practice in school in 1999. The government came out with a state sanctioned workout routine for the new millennium and it was just one of those things – in ‘99 the whole world was going crazy. The gym teacher would ask us to learn and memorize the new routine. The whole movement was so goofy compared to what we had before. I thought it was ridiculous. The title is a direct translation from the Korean and it was like, “so what, we have to do this now for the next thousand years?” I remembered it much later in 2014 and I started doing it every day as a practice. Once I started doing it, I thought about it as an artist and what it meant to be doing this routine now. So I brought it into the green screen room and shot myself doing the routine. I thought how does it work if I multiply myself? In my work I’m always multiplying stuff, but this time I multiplied myself.

LZ: What are some of the references that you look to? I can’t help but see parallels between Hieronymus Bosch, or early western Medieval paintings. Are there specific cultural, film or art historical references that inspire you?

Y: I look at a lot of medieval paintings. I really like how unnatural all these humans are depicted. I think the concept of absurdity back then in humanity is completely opposite than now, but i’ve also seen parallels in a lot of manga where the depiction of human emotion is presented in very absurd or awkward ways. I was immediately hooked on how awkward the portrayal of human emotions are in Medieval painting. But when I studied it I started to see the similarities between manga and Medieval painting – how they looked the same but came from totally different and opposite places in time.

I also really like going to grocery stores in a foreign place. But even that is getting less and less exciting because wherever you go they have more of the same thing. Yet there is still a little bit of magic there. People are still slightly different and have different customs that can be visible through product packaging, and I like to find that gap. I also like tourism, or how a place promotes what they have, through souvenirs or advertisements. I think that is super fascinating especially for me, because when I was growing up I relocated so many times I didn’t feel like I had roots in any one particular place. I think it’s really exciting to see how people promote what they think they have.

K-pop is also super interested to me, because it’s something I grew up with and now it’s influencing a lot of teenages around the world. It’s really fun to notice how this transition happened. K-pop used to be only for teenages in Korea but now a lot of these bands care less about the people in Korea and are looking to more global audiences while still reinforcing the idea of Koreanness in what these bands are selling.

Yaloo, Red Ginseng V1, 2015

Yaloo, Red Ginseng V2, 2015

LZ: In your work there is a lot of recurring objects or themes, like using red ginseng or sebum. I was wondering if you could talk a bit about that?

Y: My inspiration comes from the products that I’m interested in – stuff that I identify with as a consumer. You know these days, we build our identity by the products we consume. Red ginseng is something that I grew up with that I hated. Because I had to take it all the time and it tastes bad, but it carries this mystical quality. I think science is a bit better now in knowing what red ginseng does, but we all know and believe that it does something good for our body. In duty free shops in Korea it’s crazy, there are red ginseng sections that are these gold plated, blingy shops. I really like how the red ginseng plays a role in Korean culture as a consumable product. It used to be that it was only for royal or important people, but these days it’s mainly targeted as something fancy that anybody could afford. So I like the transition of its perception as this mystical thing with healing power that has translated into our time. In the end things just stay the same but their packaging changes their form.

Yaloo, Yaloohouse, Yes! Sebum, Documentation, Whistle, Seoul, South Korea, 2017

And sebum, it’s actually the same wherever you go, the name just changes. Sebum is a rare word because it’s a very professional term. In Asia, it’s how they express their desire for a perfect surface. In Korea and in Japan especially, people really wanted to have clean pores and keep their face beautiful. So now a lot of cosmetics are named Sebaum. I like noticing the obsessions that are displayed in those products that became so readily available in our culture. I think it connects naturally to our body because that’s where the obsessions originate from.

LZ: Sebum is what we secrete and it’s all related to consumable goods and that sort of mish-mash of consumerism that is also directly tied to animation – its role in selling products and even package design. How does value play into your work when you are dealing so closely with consumerism and products? How do you consider the value you place on an object, versus the value that you see within consumable goods?

Y: I have mixed feelings and thoughts about this. As much as I feel like I hate it, and I work against it, like half of me also loves it. I think those mixed feelings show in my work too because it’s often very playful, but I also show very disgusting images that are at the same time very celebratory. So I guess for now I’m really responding to consumerism and trying to make sense of what I’m doing, and what we are doing societally.

LZ: How did you end up taking elements from your animations and video collages and making them into tangible objects as well as reproduced consumable products?

Y: Whatever I create as the end product is immaterial. I always felt that something is missing. When I create screens it takes me months to plan, build and make, but then I have to demolish them because I can’t take them with me. So I wanted to make something physical. To make something in silk was natural because it is so light and beautiful. I create a 3D digital collage first before animating everything, so It’s already part of my natural process.

LZ: Do you see these physical objects as a kind of extension of the world you’ve created? Or as products within the universe you create, in a way that allows the viewer to take something away with them?

Y: Yeah, it was totally natural for me to think in that way. With a lot of my early work I would create something that people could take away. For example, I once created a virtual mountain for Chicago because Chicago doesn’t have any mountains. It was a video mountain, and I printed rocks patterns and made rock bean bags for the installation. When you’d leave the exhibition I made a little mountain for the spectators to take away with them.

LZ: What projects are you working on now?

Y: Now I’m working on a collaborative project called Remoto, plus Charm For Heart with my partner Pablo Monterrubio who has invented a new VR system. Well, it’s more like a hack using a security camera and a drone camera with a live feeding video helmet. It’s kind of like a haunted escape room. The idea is really about your body and the mechanical eye in our time. So we’re collaborating to create a bigger experience. We have sculptures within the system and it’ll be an extended version of my Yaloo Charm for Heart project

Yaloo & Pablo Monterrubio, Remoto + Charm for Heart promotional, still, Chicago, 2018

Yaloo & Pablo Monterrubio, Remoto + Charm for Heart promotional, still, Chicago, 2018

LZ: Are there particular animators or animation that really inspires you?

Y: One artist I can think of Miwa Matreyek from Cloud Eye Control. She does projection mapping theatre performances. When I first saw her work, she blew my mind. I really admire what she does because her narratives are super magical and fun. Also Jonathan Monaghan because I really like his animation. Katie Torn is fun. Han Han Li is also great because she might be the only hand-drawn animation artist that I know that I like.

There is also Rosa Menkman – who is a member of the initial glitch movement. Two years ago when I met her, she was working on a VR animation project where a father is walking around showing his son around the history of compression, and how that relates to the social politics of our time. It’s really great. I also like Jodi Mack’s work, because her style is super analogue. I went to a screening series at a glitch festival once and she had this glitch project with stop motion in the program. I really like these interventions where you are working with new ideas about new technologies but you find a way to source from something analogue to explain what’s happening now. Jodie Mack’s work is really smart at doing that.